Who invented bourbon?

Was It even invented in Kentucky?”

The history of bourbon is shrouded in mystery. There are many myths and educated theories regarding its origin. Authoritative bourbon historians tend to agree that Elijah Craig didn’t invent it. But before we dive into the topic, we must first decide what it is and what’s relevant to the investigation of who invented it. Are we concerned about the product itself or who first used the name bourbon to describe it? Those are two entirely different topics, both worthy of conversation. Because I titled this article “Who Invented Bourbon,” I think the relevance is on the product itself.

Bourbon has two distinct qualities as a whiskey: 1st, it has to be made primarily out of corn, and 2nd, it has to be aged in newly charred oak barrels. This is close to the legal definition, but that’s not what I’m going for; hence, I didn’t say new American White Oak charred barrels. Before any statute legislatively defined this product, it existed as a product of its environment. In the pioneer days, barrels would have been reused a lot. The quality that made it bourbon had little to do with the actual age of the barrel and more to do with the fact that it was freshly charred. One theory of bourbon is that pioneering distillers charred barrels that had held other products to get rid of off-putting odors. Okay, so before we get more in-depth on barrels, let’s talk about what whiskey would have looked like on the American frontier in 1820.

Something to keep in mind is that glass bottles were expensive in the early nineteenth century because they had to be handblown. It wasn’t until the 1880s that bottle production was semi-automated. Grocers and apothecaries purchased whiskey by the barrel and dispensed it from the barrel. If you bought whiskey for your household, you would have done so by refilling a one or two-gallon stoneware clay jug or a two or three-gallon keg (made of wood or ceramic) at the grocer. This is not to say glass bottles didn’t exist. They did, but they were expensive and were reused rather than disposed of, like ceramic jugs and oak kegs. In fact, Old Forrester (original spelling) is claimed to be the first bourbon widely sold to consumers in a bottle in 1870. Jim Beam didn’t start bottling until the 1880s

Name brands in American whiskey were essentially unknown in the early nineteenth century. Grocers were better associated with quality whiskeys than distillers as they were the distributors, and their whiskey wasn’t generally branded according to who distilled it. So, in the first half of the nineteenth century, American whiskey wasn’t typically sold in bottles or by the brand name. Instead, the consumer brought their storage vessel to the grocer or the distiller and had it filled. Now, here’s the thing. If you bought your whiskey directly from the distillery, your whiskey was probably clear! If you purchased it from a grocer or other middleman, it was likely anywhere from a light straw color to a deep burgundy color. This is because the middleman who bought it in bulk purchased it in a barrel, and the barrel imparts color.

The barrel was a practical instrument of whiskey commerce. The barrel was, in fact, used as a primary shipping container for many products. Brined fish, butter, sugar, cider, beer, and nails are just a few examples of many products stored and transported in barrels. Today, when we think of barrels, we think of whiskey and wine, but that wouldn’t have been the case 150 years ago. They were simply shipping and storage containers for just about anything. Whiskey just happened to be a product that gained flavor and improved in palatability while in the barrel. But the point here is that early American whiskey was all across the spectrum when it came to color because bourbon acquired its color from aging. Aging wasn’t yet intentional but rather the product of shipping and storage.

One of the earliest references to whiskey being aged in charred barrels comes from a letter written by a Lexington grocer, J.M. Pike, requesting another order of barrels of whiskey from a Bourbon County distiller named John Corlin in 1827. In the letter, Pike says he has heard that burning the barrel inside will improve the flavor of the whiskey.

A grocer rather than a distiller would recognize that the barrel positively impacts the whiskey’s flavor as it was ultimately the grocer that most widely distributed the product to the consumer. But charred barrels were already being used and standardized in European brandy production and brandies such as Cognac and Armagnac were hot imports in New Orleans. This brings us to another theory of bourbon’s name: it was named after Bourbon Street, New Orleans, being that so much corn whiskey was shipped to New Orleans and sold on Bourbon Street. Merchants would have known that the darker-colored Armagnacs and Cognacs arrived in charred casks. It would have been intuitive to observe that charred casks lent a darker color and that the darker-colored spirit was generally more desirable.

While it’s plausible that barrels were sometimes charred to remove unwanted odors, and these could have sometimes been used for storing corn whiskey, which was later discovered to yield an excellent product, the knowledge that charred casks produced superior European brandy was already known.

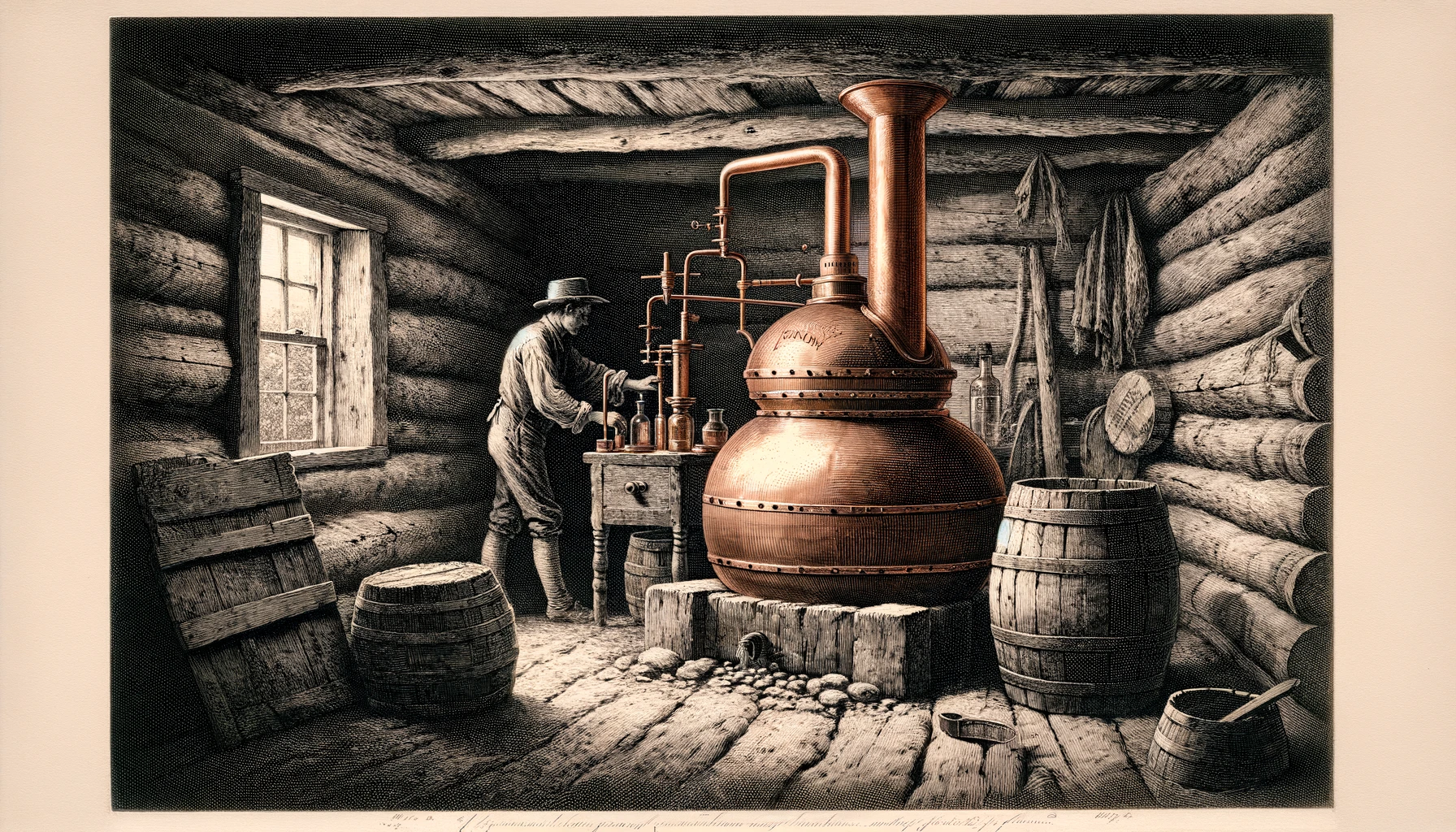

So, let’s back up a bit. What did the average early nineteenth-century distillery look like? Many early pioneers of the Western Ohio River basin (encompassing part of Indiana, Kentucky, West Virginia, and Tennessee) would have utilized small stills on their farms. In fact, the following excerpt is taken from the History of Dubois County (Indiana) by Geo Wilson in 1910:

“Apple brandy, peach brandy, and corn whiskey were not subject to a government tax in pioneer days…Many farmers made their own liquor…Nearly every farmer had cows, and a distillery.”

There is also a reference to Major John Haddock’s operation of a distillery near the Buffalo Trace in that county in 1837. Note: Buffalo Trace was a pioneer trail that served as a road stretching from part of Illinois, through Indiana, and part of Kentucky.

The idea that corn whiskey wasn’t restricted to Kentucky shatters the Bourbon County origin of bourbon. Unless, of course, Indiana whiskey wasn’t being shipped in charred barrels, and maybe it wasn’t. Still, we know Indiana whiskey was being shipped to New Orleans just like Kentucky whiskey. We also know that corn was the primary grain for Indiana whiskey, like it was for Kentucky whiskey. And we can safely presume that oak barrels were the means of transport like they were for everything else.

In the History of Sullivan County (Indiana), Edited by Thomas Wolfe in 1909, we find a reference to an advertisement in the local newspaper from December 1816, advising of the opening of a new distillery in Knox County (adjacent) with corn whiskey being on sale for .75 cents a gallon.

In the History of Lawrence and Monroe Counties, Indiana, published in 1914 by B.F. Bowen, there are several references to distilleries, but one of note mentions Hugh Hammer buying property for a distillery in Lawrence County in 1825 and shipping his whiskey on flat boats via the White River (which meets the Ohio River) to New Orleans. The chapter mentions three other distilleries opening up in that area of the county in the early 1830s. Another section of the book mentions that one of the first businesses of Bedford, Indiana, was a distillery that produced three barrels of whiskey a day, which was shipped to Louisville. The book mentions that this distillery was a significant consumer of local corn (10,000 bushels a year).

My point in bringing up these references is that Kentucky is far from having a monopoly on the origins of Bourbon Whiskey. Consider that Dr. James Crow’s Old Oscar Pepper Distillery only produced about three barrels of whiskey daily, according to Michael Veach’s book Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey. The Bedford, Indiana distillery was on par in production with this Kentucky legend but even earlier.

But even more interesting: Michael Veach claims the likely inventor of bourbon was probably not a distiller but a grocer or merchant, and to that end, he points to a likely culprit: Louis and John Tarascon, who had established a warehouse below the Falls of the Ohio and established trade with New Orleans around 1807. Considering that the Bedford, Indiana, distillery was also shipping its product to Louisville, it was most likely being redistributed. And since we have reference to another Lawrence County, Indiana, distillery shipping product to New Orleans, we can reasonably speculate that the Bedford corn whiskey was being shipped there. It’s therefore highly likely that the Tarascon brothers and other merchants were aggregating Indiana whiskey with Kentucky whiskey and shipping it on down the river.

The reality is that Bourbon wasn’t set to any legal standard until the Bottled in Bond Act of 1897. Until then, there was an idea that bourbon was a corn whiskey aged in charred oak barrels, but those standards developed organically over decades. There’s a theory called simultaneous discovery that observes that most inventions and discoveries occur independently and simultaneously by different persons rather than a single person because there is a confluence of societal and technological factors leading to the discovery, which affects a wide range of people and not a single person. The simple fact is that rugged pioneers moved into the Ohio River Valley, and they possessed the knowledge to distill from grains; corn was the most prevalent and easy-to-grow grain in this region; the product was stored and traded in oak barrels out of convenience, but merchants learned that whiskey shipped in charred casks had a more eager consumer. There was no inventor… it just happened!