We are deceived if we believe the cocktail is no longer medicinal. It might not cure typhoid, rheumatism, or nervous fever, but it’s a potion for the mind. Alcohol, when given the right environment, blurs the boundaries of imagination, and sometimes, such transformational power is a potent medicine. The soul, after all, is found in imagination, which is not to say it doesn’t exist.

Medicine shows and patent medicines have a dubious reputation, which too often overshadows their glorious cultural roles. Yes, progress is a thing, and so too is medical malpractice and human suffering, but that does not mean we need to devalue the narratives of our past. Stories are handed down from one generation to the next–they become mythologies–and our behaviors are often role enactments of these narratives. The connection between the past and the present is not always clear, but there is an abstract root to those stories, which lurks below conscious awareness. The stories we’re talking about today have a shared genealogy; on the surface they may appear different but with close inspection, the sociology and psychology of it reveals that not all that much has changed.

My argument here is that the medicine shows and patent medicines of the past had an amazing and timeless quality despite their quackery that endures, and is even celebrated, today. No: it’s more than that! The medicine show is alive and well. You see, we too often forget the soul in our jump for progress. I’m not talking about anything supernatural, but rather, I’m talking about the stories that make us who we are–our cultural identity. So here it is: the medicine show was the speak-easy of its day. Its literal product, the patent medicine, served as a common cocktail ingredient, and was often a cocktail or cordial in its own right. I’m not only arguing the analogy; I’m arguing that these things share the same cultural genealogy, and thus, our imbibe culture is directly a product of both the patent medicine and the medicine show.

When the Doctor Prescribes a Mint Julep: Patent Medicine and the Cocktail

The other day, I was reading the 1860 Edition of Gunn’s Domestic Medicine for another research project. In the course of reviewing this book, I read that either rum or whiskey should be given as a “stimulant” to slow the heart of those suffering from “nervous fever.” Gunn also prescribes a hot toddy with peppermint for convulsions and gives numerous guidance on preparing tinctures of herbs with whiskey or other spirits for curing or treating various ailments. Gunn’s book is not exceptional; it prescribes to the knowledge of the times. Any medicine book written in the nineteenth and eighteenth centuries would be incomplete without prescriptions for liquor, tonics, herbal elixirs, and bitters.

Angostura bitters was once marketed as both a digestive and a treatment for malaria. It’s commonly claimed in the world of bartending that there are two types of bitters: aromatic and potable. Aromatic bitters are used to flavor cocktails, while potable bitters are meant to be drunk neat as an aperitif or digestif. The claim is sometimes made that most potable bitters originated as cures or medicines while aromatic bitters were developed to flavor cocktails. This is an incorrect assumption. For one, both aromatic bitters and potable bitters serve to flavor cocktails. Aromatic bitters may be a bit more concentrated, but a few cocktails use aromatic bitters as their primary spirit or, in that case, their primary liqueur. But the actual case to be made here is that the most famous aromatic bitters have their roots as patent medicines. The case for Angostura has been made, but the same is true for Peychaulds. It was started by the owner of an apothecary who sold his bitters for nervous disorders and stomach ailments.

Not long after markets for Angustora Bitters and Peychaulds Bitters became widespread in North America, we find the first use of the word “cocktail.” A cocktail was a specific drink for the first half of the nineteenth century. It consisted of a jigger of spirit, a spoon of sugar, and a few dashes of bitters. In this era, two of these three ingredients were regarded as medicinal. It’s a natural assumption that sugar was a simple means of making the concoction–the cure–more palatable.

While I haven’t found an explicit reference to “cocktails” being prescribed as medicine in nineteenth-century literature (and I can’t say I’ve really looked), I’ve found numerous references to whiskey, rum, and brandy being prescribed and treated as such. Considering that the bitters used to flavor cocktails were explicitly advertised as medicines–there is no reason to believe cocktails weren’t created medicinally. It does need to be explicated here that I use the word cocktail to refer to a specific drink, the one we recognize as the old-fashioned, because we do find reference to other beverages, which would be considered cocktails today, as medicinal (such as the toddy).

The mojito is another drink we can safely assume existed medicinally in some form before it was prescribed recreationally by cocktail manuals. The British Royal Navy prescribed rum and lime to its sailors to prevent scurvy. Any common physician of the day would innately know the medicinal benefits of throwing some mint into the concoction, as there are many references to the medicinal benefits of mint in the medical literature of the time. The mojito wouldn’t appear as a written recipe until 1927, under the name Mojo Criollo. Still, it possessed common ingredients readily available in the Caribbean that were widely believed to be medicinal by learned men and slaves alike. It’s long been rumored that the mojito existed as early as the 1600s as a medicinal remedy for sugar plantation slaves. Still, good ole Anglo medical literature would have easily prescribed the concoction.

Many patent medicines would have been proofed down spirits of one sort or another, slightly sweetened to make them palatable, and spiked with medicinal herbal tinctures. Considering that bitters are essentially herbal tinctures, some of these concoctions probably tasted like a bottled old-fashioned. They were, in essence, bottled cocktails. Some had the extra stimulating ingredient of cocaine or the extra intoxicant, opium. But aside from speculating that some patent medicines were essentially bottled cocktails, most met the definition of an herbal liqueur: a maceration of spirit and herbs.

But debating whether or not patent medicines were themselves potable drinks is not my goal–though some clearly were. My point is that some of our oldest mixed drinks evolved as medicines, and they set the stage for the golden era of the cocktail: the glorious latter half of Jerry Thomas’s nineteenth century. For those who don’t know who Jerry Thomas is, he wrote the book “Bar-Tender’s Guide” in 1862, giving numerous recipes for mixed drinks. This was the first book of many cocktail manuals written in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

The Medicine Show

Most of the swamp root elixirs (patent medicines) were spirited herbal macerations. Wild cherry and birch bark were common ingredients, as were sassafras and gentian. The herbs were believed to have curative properties. Alcohol would have helped numb the perception of any ailment–especially when mixed with more liquor. And cocaine and laudanum made it all even better. Intoxicants and entertainment go hand in hand, and the medicine shows, as odd as they may seem, were a natural manifestation of that match.

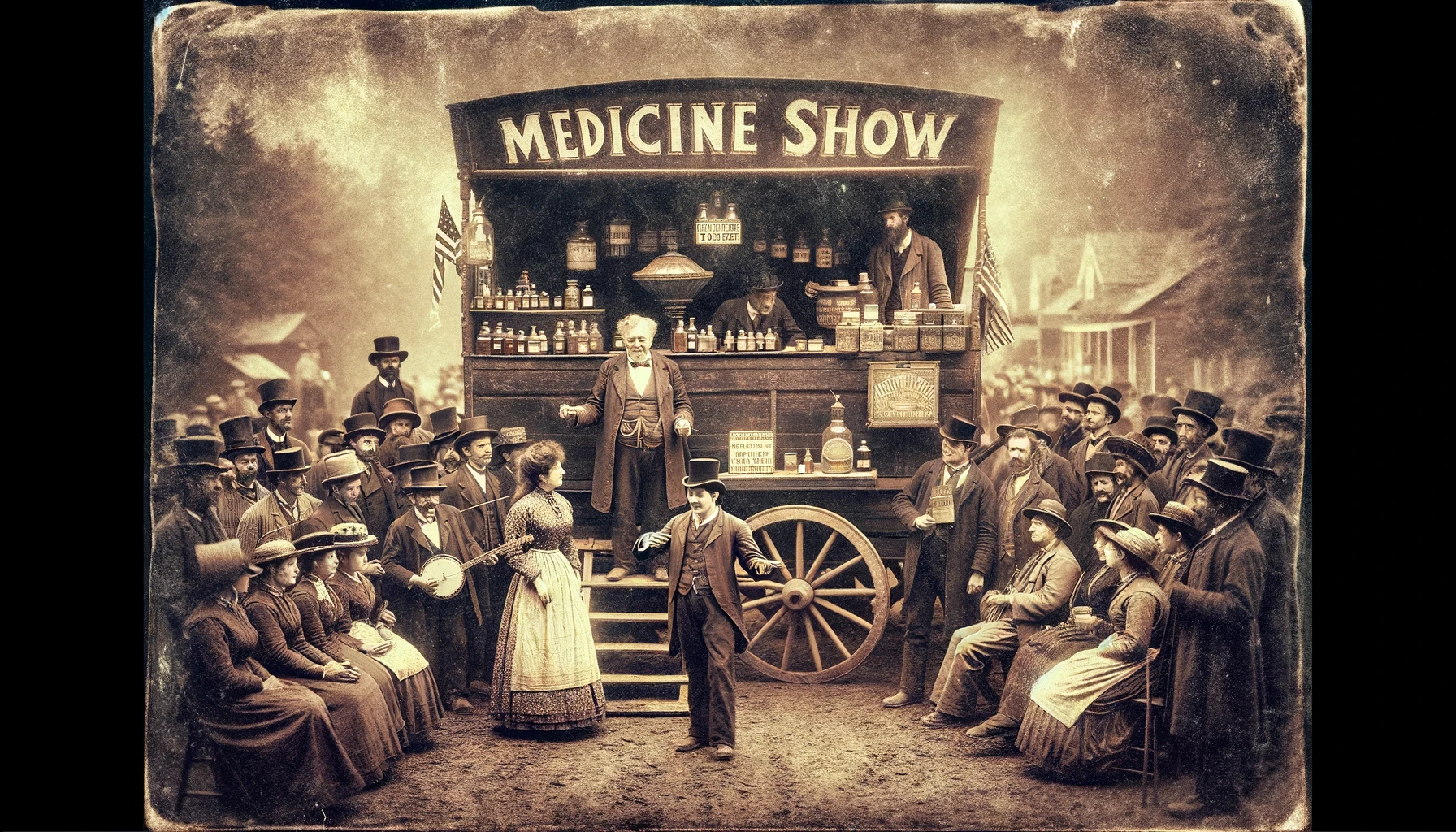

Enterprising individuals, likely those who studied the formulary receipt books of their day, created numerous curative elixirs. Grocers would have carried various patent medicines. Indeed, grocery and pharmacist receipt books offered numerous recipes to imitate the most famous of them. But the real show was the medicine show–when the enterprising creators of new cures came into town to promote and sell their energizing and life-giving elixirs. They often brought a troupe of entertainers that made the medicine show about a lot more than the herbal liqueur, pills, or liniment it promoted.

Common acts included musical performances, ventriloquism, comedy, flea circuses, dancers, and freak shows. They were traveling carnivals under the sponsorship of the medicine purveyor. The casks of whiskey and apple brandy likely flowed freely at many of these events and complemented the intoxicating potions being marketed. Cocktail historian David Woodrich, in his book Imbibe, noted that these were social events in which alcohol played a central role. For many communities, the medicine shows were the only communal entertainment they would see for months. They were an escape from the mundane, an altered reality where energy flowed, and people lowered their inhibitions. They were an escape from the mundane.

A common theme with the purveyors of patent medicines was to claim they were based on arcane knowledge bestowed by Native Americans and sometimes from the faraway Orient. Native American participants often played a central role in these shows and were hired to perform war dances, rain dances, and other ceremonies for entertainment. It’s odd that the cultures of the first people could simultaneously be so disdained yet revered. The allure and mystique of the distant, the primitive, and the arcane in these shows are reminiscent of the tiki scene in modern-day cocktail culture with its romanticism for the mysterious and primitive. The theatre of it all offers an escape from the mundane where the unknown opens the mind to a new world of possibilities.

We are deceived if we believe the cocktail is no longer medicinal. It might not cure typhoid, rheumatism, or nervous fever, but it’s a potion for the mind. Alcohol, when given the right environment, blurs the boundaries of imagination, and sometimes, such transformational power is a potent medicine (in a Lakota sense of the term). The soul, after all, is found in imagination, which is not to say it doesn’t exist. But as the Native Americans say, medicine can be good and bad. As for the medicine show, the purveyors of cocktails still look to create entertainment for their customers in order to sell more cocktails.